By David Weiner

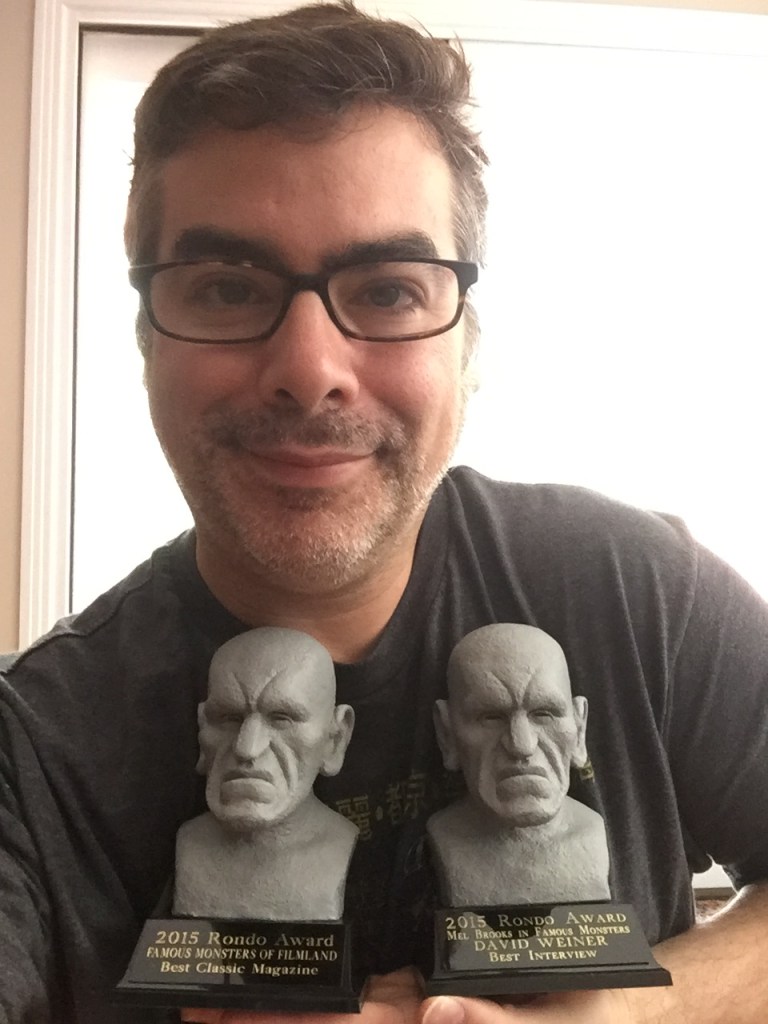

Back when YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN was celebrating its 40th anniversary, I had the distinct honor of interviewing Mel Brooks for an exclusive Famous Monsters magazine cover story. That entertaining and informative interview with the legendary EGOT would go on to win me my first-ever Rondo Hatton Award for Best Interview of the Year (2015) — quite an honor, especially because that Rondo was accompanied by a second statuette win: Best Classic Magazine, for Famous Monsters of Filmland, awarding the first year that I took over as Executive Editor of the iconic magazine.

Needless to say, I was quite proud of the double-Rondo honor that was bestowed on me (along with the hard-working staff of the magazine, of course, and the prestigious baton that was handed to me by previous Executive Editor Ed Blair).

Now that a decade has gone by since then, I figured it was time to post the original interview piece on IT CAME FROM… for posterity, as FM issue #277 is getting harder to come by and can only be found on eBay, essentially.

CLICK HERE to see the original article layout in Famous Monsters of Filmland issue #277

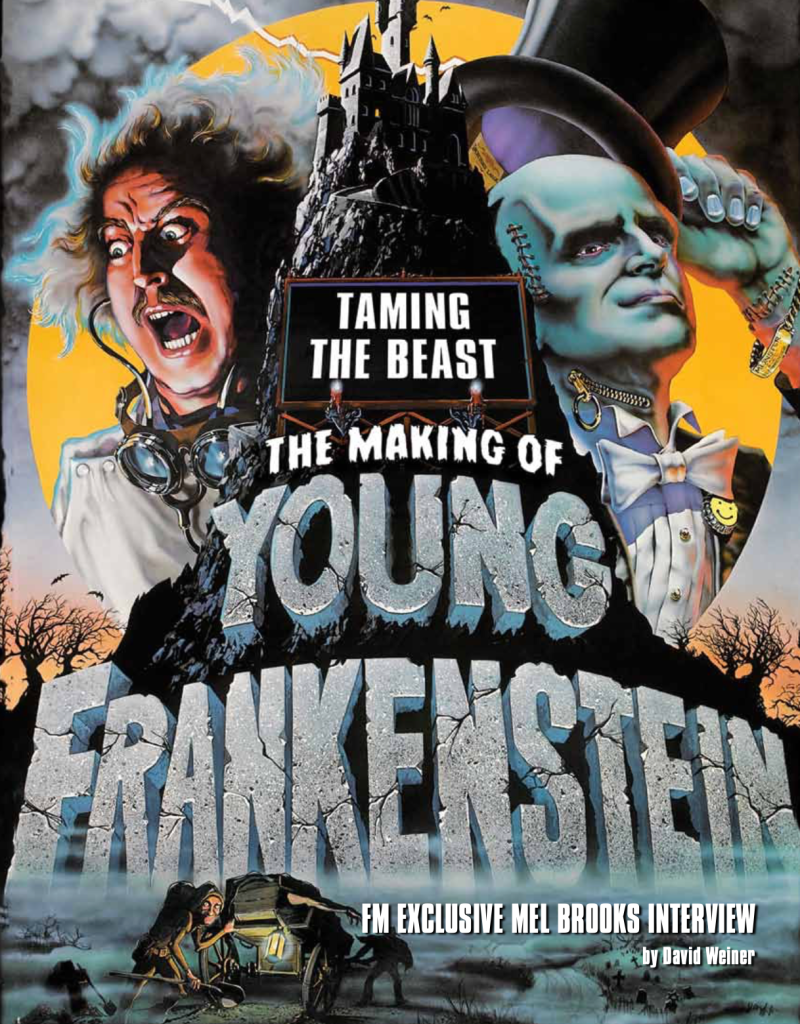

Taming the Beast: The Making of ‘YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN’

From capturing lightning in a bottle to the friction and fights behind the scenes that resulted in pure comedy genius, the legendary, timeless and tireless Mel Brooks talks to FM about the making of his horrifically hilarious, personal all-time favorite movie on the 40th anniversary of its release.

Nineteen-seventy-four was a good year for Mel Brooks. A very good year. In fact, as far as comedy is concerned, you could consider it The Year of Mel Brooks, with the one-two gut punch of his western satire BLAZING SADDLES in February followed by his hysterical take on the classic horror genre, YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, knocking out all comers and cracking up audiences senseless. No one would look at baked beans the same way, much less admire the trappings of the original 1931 FRANKENSTEIN as seriously as they once did.

The success of these back-to-back hits vaulted Mel’s career into the stratosphere, and firmly entrenched the two titles amid the top 120 films of all time in terms of box-office performance. BLAZING SADDLES lassoed close to $120 million at the domestic box office, while YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN dug up more than $86 million domestically; each on a production budget of under $3 million. Adjusted for 2014 inflation, that translates to ticket sales north of $515 million and $375 million, respectively, in the United States alone — positively “Abby Normal” figures for any comedy. Not bad for a scrawny kid from Brooklyn-turned-EGOT (member of an exclusive circle to have won the Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony award)…

“It’s the only perfect film I’ve made,” Brooks, (who was 88 years old at the time of the interview), tells FM of YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN. “No other film comes near being perfect. There isn’t a moment I would change. … It’s my finest film because it’s the best film I ever made, technically as well as emotionally; an artistic combination of emotion and the art of moviemaking.”

You can trace the seeds of Brooks’s brilliant parody all the way back to 1931, when he saw FRANKENSTEIN at the tender age of five — and was never the same. “Scared the shit out of me; I was really terrified,” he says with a laugh, admitting that he was “much too young” when he saw it, “but my brother Lenny was going, and he took me.” Shaken by the horror, the humanity and the literal electricity of seeing Mary Shelley’s Gothic tale on the big screen, this indelible experience ultimately motivated Brooks to be incredibly respectful when making fun of one of the greatest horror pictures ever made.

“When you do a satire of a genre, you’ve got to love that genre,” explains Brooks. “It’s got to mean something to me.” With that in mind, Brooks approached the YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN material much in the same way that he approached BLAZING SADDLES: With respect. “Every Saturday morning I saw three western films when I was a little kid, and they saved my life. I loved them. Hoot Gibson and Ken Maynard, George O’Brien, Tom Mix — these guys were incredibly important to me. Buck Jones. There wasn’t a western hero I didn’t love, or a western villain dressed in black — Frank LaRue — that I didn’t hate. I really had fun with the western and I was saluting it. But the intensely beautiful work of [FRANKENSTEIN director] James Whale had to be recognized.”

YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN wasn’t actually Mel’s idea. It was Gene Wilder’s. The two friends, who initially met through Brooks’s then-girlfriend (and later, wife), Anne Bancroft, had already discovered that they a potent chemistry working together on THE PRODUCERS and BLAZING SADDLES.“ Me write, he do. Me direct, he do,” jokes Brooks. “If we were in a huddle and I chose play 14, you know, and Gene gets the ball, nobody could carry it better.”

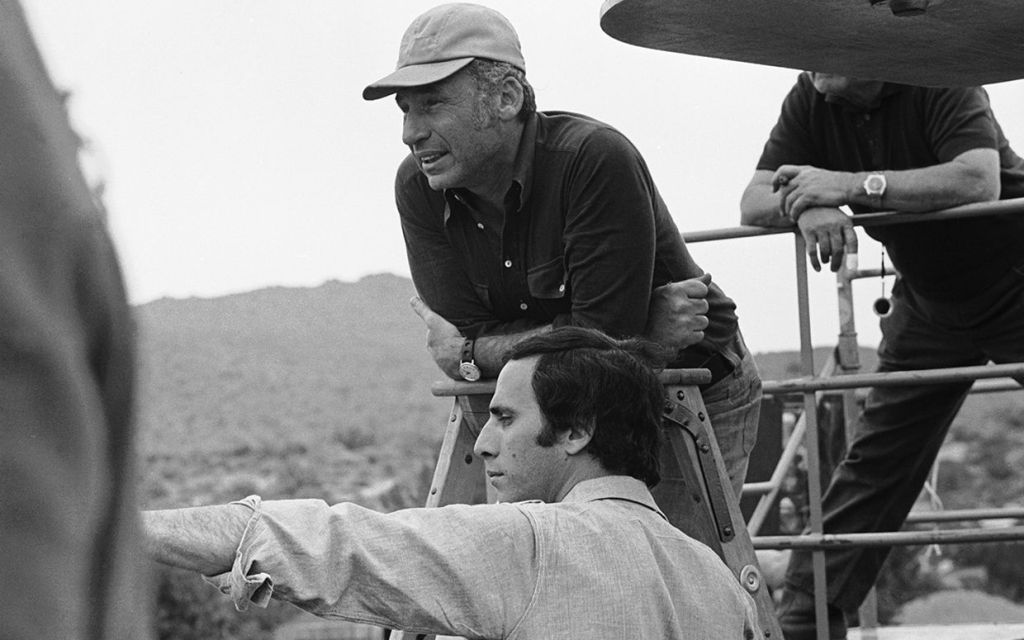

It was during a particular nerve-wracking day on the set of SADDLES that the two decided to pair up for another genre satire of sorts. Brooks recalls, “We took a break; it was 4 o’clock in the afternoon, it was one of the last scenes, a fight between the bad guys and the good guys, and it was hot, and it was a tough day. I was going to do it three or four more times in the master and add some hidden cameras for some coverage, some closer shots, and we broke for coffee. Gene was sitting there, back up against the jailhouse building, and he had a yellow legal pad, and he was writing with a pencil. So I said, ‘Let me help, let me dictate: You can hardly see the sky, it’s filled with German bombers.’ (laughs) Gene said, ‘No, no, it’s not that.’ He really liked war pictures, especially in England. So I said, ‘What are you writing?’ He said, ‘I had an idea that the grandson of Victor Frankenstein would be ashamed of the stupidity, futility, insanity — you know, he’s a scientist, he doesn’t believe in animating dead tissue. Dead is dead.’ That’s what he was going to call it to begin with: DEAD IS DEAD was the movie. So, I looked at it, it was a few pages, and said, ‘Flesh it out. I’m interested. I’m on board. I like it. I like the idea, I think we can work it out. I’m doing a big satire of the other westerns, why not do a real big, definitive, satiric movie on FRANKENSTEIN and DRACULA, you know, on a horror movie.’ He fleshed it out and came back with another title that he liked, called YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, and I liked it too. And because he had the original impulse, I said, ‘Let’s write it together and you’ll get first billing.’ He said, ‘No, no, no, you’re the writer.’ I said, ‘No, that’s the way it’s done.’ So he got first billing on the screen for writing it.”

Like discovering Dr. Frankenstein’s secret diary, their first foray behind the typewriter together turned out to be as fortuitous as their onscreen collaborations. The wild and crazy ideas flowed non-stop, and a story was soon fabricated about how Dr. Frederick Frankenstein (pronounced Fronkensteen, thank you very much), to be played by Wilder, travels to Transylvania to inspect the estate he inherited, only to find himself following in the exact footsteps of his infamous, mad scientist grandfather — complete with grave robbing, a secret laboratory, a towering re-animated corpse, torch-and-pitchfork wielding townsfolk, and a sidekick named Igor. Or, rather, “Eye-gore.”

“It was hand-in-glove. We worked beautifully together,” say Brooks. Beautifully, that is, until their one big blowout; creative differences that put in jeopardy what would become arguably the funniest sequence in the movie: “We only had one enormous fight in the writing of YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN. We had a big, big fight. I decided after fleshing it out and getting it storyboarded and everything that ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ was too funny, too silly, and would just hurt the salute to Mary Shelley and to the early James Whale FRANKENSTEIN movies at Universal. I said, ‘Gene, that’s tearing it. ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ is really making fun at it, not with it, and I think we’ve gone too far. I’m not going to do it.’ He let a week go by, and he said, ‘You know what? Why don’t we get a little extra money. Why don’t we shoot it, and then if we think, in the context of the picture, that it’s too silly and too stupid, too outrageous, and hurts the texture of the salute to James Whale, then we’ll take it out.’ So I said, ‘Okay, that makes sense.’ He knew he was dealing with a crazy man. … And then [after it was shot] we saw it together and I turned to him and said, ‘You know, Gene, that’s the best thing in the movie.’ So god bless him for his struggling [and] fighting with me. Otherwise, there wasn’t a moment that we disagreed on.”

Brooks has been a fixture in practically every film he’s made during his long career. The son of Russian Jewish immigrants and a natural performer who cut his teeth on the Catskills crowds, he would regularly star in his own pictures, like in SILENT MOVIE, TO BE OR NOT TO BE, and the Hitchcock parody HIGH ANXIETY, or insert himself and steal the scene, whether as a Hasidic rabbi in ROBIN HOOD: MEN IN TIGHTS, an Indian Chief/“hurumphing,” cross-eyed governor in BLAZING SADDLES, as President Skroob and Yogurt in his STAR WARS spoof SPACEBALLS, or playing no less than five historical figures in HISTORY OF THE WORLD: PART 1. But Brooks is conspicuously absent from the screen in YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, and that decision stemmed directly from a demand made by Wilder. Brooks recounts, “Before we had our first writing session, Gene said, ‘I’ll do it with you on one condition — that you’ll promise me you won’t be in it.’ So I said, ‘Wait a minute, am I so bad?’ He said, ‘You’re not bad, but you’re always breaking the fourth wall. I’m afraid you’ll be in a suit of armor, flip up the visor and say, ‘Hiya folks!’ I don’t want to break the fourth wall.’ So I said, ‘Okay, alright, I won’t be in it.’ That was the deal.” Still, Mel found his way into the picture by howling off-screen as a werewolf, mimicking a cat hit by a dart, and as the voice of Victor Frankenstein.

Wilder also had one other requirement alongside Brooks removing himself from any screen time. “[Gene] said the other condition was that the film had to be in black and white,” says a jovial Brooks. “I said, ‘That was the condition I was going to bring to you!’” Making YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN in black and white, rather than in color, was a major sticking point for the creative partners. They wanted to remain true to their 1930s source material, but Hollywood and its audience had long since graduated to color and, like the transition to Talkies, there was no turning back. As far as the studio brass was concerned, nobody wanted to pay to see a movie in black and white — and Brooks and Wilder’s insistence that their audience demanded it almost cost them the whole project.

“We made a deal with Columbia,” recalls Brooks. “We needed at least two million dollars in those days, a lot of money, to make the movie. And the most they could come up with was $1,750,000. So I said, ‘Look, Gene, let’s promise them that [we’ll do it for that figure], then go to two million.’ What could they do? They’re not going to throw the movie out — they’ll lose all their money. … We didn’t sign anything yet, but we all shook hands in the Columbia boardroom on Gower in Hollywood, where Columbia Pictures was. On the way out I said, ‘Okay fellas, this is great. We’ll start Monday talking in earnest, and oh, by the way, we’re gonna make it in black and white.’ Just tossed it on the way out. And a thundering herd of Jews followed me down the hall, screaming, ‘Wait! Wait! Don’t go, let’s talk!’ And we were there for another five or six hours; they were trying to talk [us] out of it.”

In love with the project and determined to make the YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN deal happen, the Columbia execs came up with a ploy to make everybody happy. “They said, ‘Here’s what we’ll do’ — it was a compromise — ‘we’ll make it on color stock, and in the United States’ — not in Canada, not in Mexico, not in the rest of the world — ‘we’ll make it in color and diffuse it to black and white. We’ll promise you that in the contract. And then all the rest of the world will be in color,” explains Brooks. “We nearly bought that, and then we decided, ‘No, no, it’s got to be on black-and-white stock,’ because I did some research and found out that it’s not black and white — it’s kind of dark blue and white when you do that; the whites are gray. It wants to be in color, that’s all there is to it. So we said no. And Gene and I looked at each other — we were pretty damn brave — he said, ‘It’s a deal-breaker,’ and I said, ‘Well, then, the deal is broken.’ … And we left.”

Rather than “Liiiife!!!!!” for the project, it was back to the drawing board. Following the mega-success of BLAZING SADDLES, Columbia was without their Mel Brooks comedy, and Brooks and Wilder were without a studio to back and distribute YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN — all because they couldn’t agree on the same film stock. But principle is principle. Michael Gruskoff, the film’s producer, brought the project to Alan Ladd Jr., aka “Laddie,” at 20th Century Fox — the head of creative affairs and later president of the studio who was instrumental in green-lighting such classics as STAR WARS, THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, BREAKING AWAY and ALIEN during his reign.

“He read it and he loved it, and said, ‘I want to do this,’” remembers Brooks, who had quickly become trepidatious about his and Wilder’s creative deal-breaker. “I said, ‘Laddie, if you do this, I’ve got to tell you right now before you even get started, it’s going to be in black and white or we’re not going to make it.’ And he said, ‘It should be in black and white. I saw it in black and white [when I read it].’ Then I said, ‘We were going to make it for two million at Columbia,’ and he said, ‘I’ll give you $2.2 million.’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s generous!’ After that, I made my next three or four movies with Fox because I knew I had the right guy to distribute my movies.”

With a deal for financing and distribution secured, it was time to get down to the brass tacks of casting and crewing up, which turned out to be a serendipitous endeavor. “First of all, we had the greatest cast in the world,” crows Brooks. “Peter Boyle playing the monster, he was magnificent. And we had Marty Feldman from THE MARTY FELDMAN COMEDY MACHINE … I was in London and I went over and saw this guy — and those hardboiled eggs going out both sides of his face (laughs) —and I said, ‘Gee, this guy’s funny. He really is funny.’ And it so happens — this is a strange story — Mike Medavoy, he was an agent at ICM, I think … he had Gene Wilder, Peter Boyle, and Marty Feldman — that’s just amazing — the trifecta that was perfect for the movie. He was so overwhelmed when he suggested [that I use all three of his clients] and I said, ‘It’s a deal.’”

The rest of the cast came together nicely, like stealing the brains of scientists/saints at the Brain Depositary, rather than absconding with abnormal ones. A close pal after starring in THE GRADUATE opposite his wife Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman was originally intended to play Inspector Kemp, with the comical wooden arm and eyepatch sporting a monocle. “He was absolutely brilliant,” beams Brooks. But when Hoffman proved to be unavailable, “We held auditions and got lucky — we found this guy Kenny Mars, who was a genius with a great accent. Gene found Teri Garr in a movie and she looked perfect for [her role as Frankenstein’s personal assistant, Inga]. And I had Madeline Kahn from BLAZING SADDLES, so I knew I had the best. I asked her to do me a favor — [Frankenstein’s fiancee] wasn’t the lead, but it’s a good part. We really covered it, you know?”

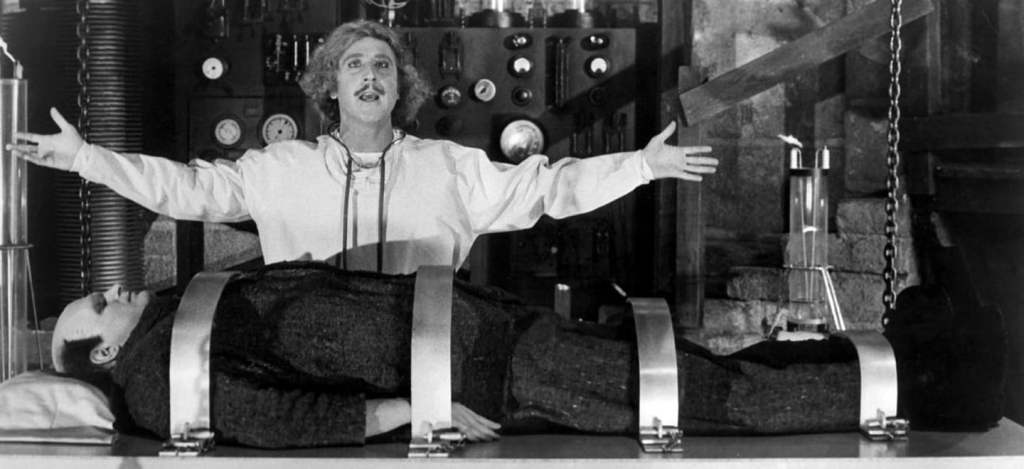

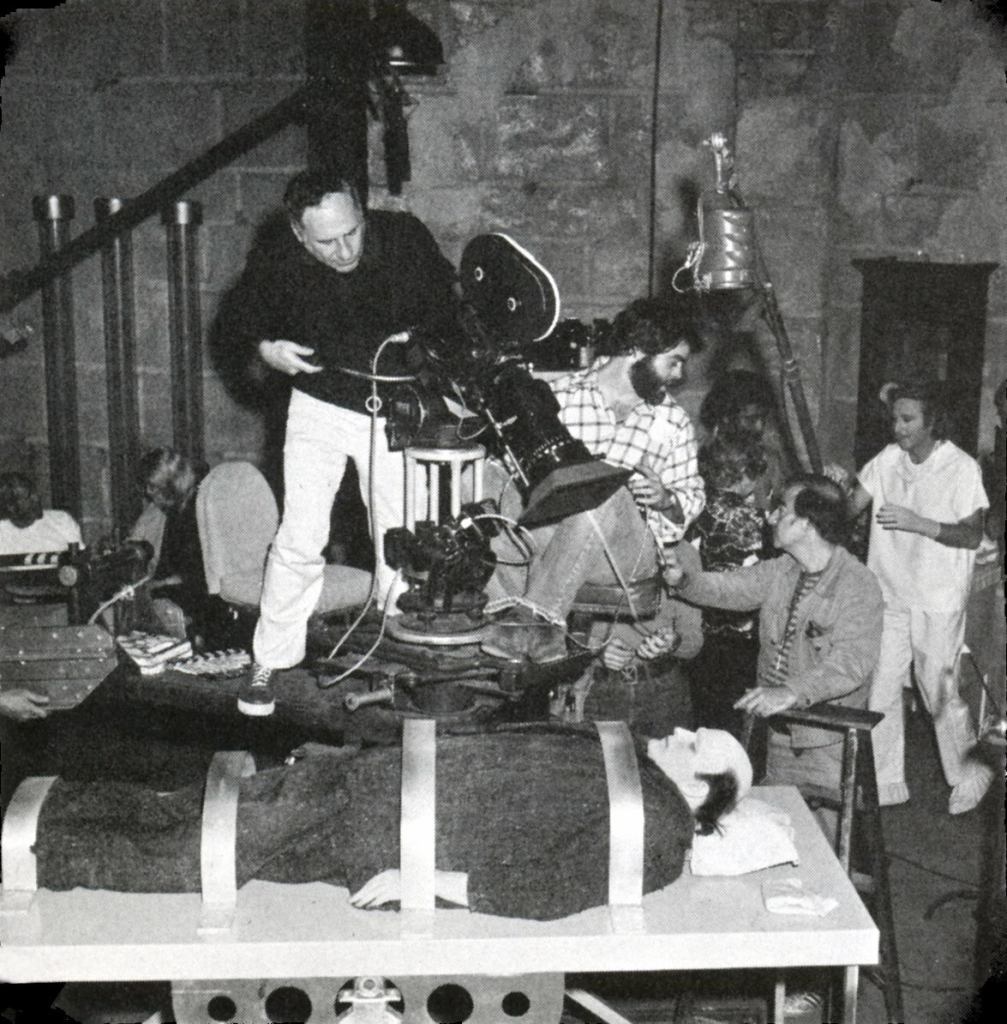

Once principal photography was underway on February 26, 1974 — shooting at the University of Southern California, MGM Studios and on the 20th Century Fox lot in Century City, CA — the YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN set was magic; a place where those associated with the film would hang around even if they weren’t working that day — just to see what would happen next. “It’s the way we all gave ourselves to it,” explains Brooks. “We gave ourselves unreservedly to it, morning noon and night, emotionally, caring about it. Gene Wilder was never better. He was absolutely Promethean in the role. He was as nutty as you could be for a mad professor. You can’t be any crazier than Gene was in that. But there was also the other Gene — in the sporting jacket, and at breakfast, taking a tray of salmon to Teri Garr, saying, ‘Kippers?’ — gracious, sensitive, intellectual, good-natured; completely opposite of the madman who wanted to kill the monster for not being alive.”

Making the signature sound of horses neighing at the sound of Frau Blucher’s name, Brooks continues: “Cloris Leachman gave herself to that movie. She was such a friendly gal, and so funny and so wild, but when she was Frau Blucher, [she] never got out of character. I mean, you’d say, ‘Goodnight,’ she’d say, ‘Goodnight’ — she was stern, she was crazy, so she gave herself to that movie. … I think she had just won an Academy Award for THE LAST PICTURE SHOW. And a great actor like Gene Hackman — to this day, half the people who see the movie don’t know it’s him as the blind man. They have no idea. He really became that blind man. He never blinked once at the camera saying, ‘Remember me, folks? Gene Hackman!’”

As for the artists working behind the camera, Brooks enlisted a roster of capable hands at the top of their game. “Think of the makeup. Think of the lighting. Think of the sets. Think of the sound. Every aspect, they were devoted to it. Never better. … I got Jerry Hirschfeld [as my cinematographer], who had done some black-and-white movies that I saw, and I said, ‘This guy knows what he’s doing.’ He was a doll and easy to work with, and we only had one fight. I had a big fight with Jerry. Dale Hennesy, our genius [production designer] — he died of drink, what a guy, what a guy — he made the set with sweating stone. What a set. In the laboratory floor, Dale built these stones to kind of look [realistic, so they were] slightly uneven. When Jerry’s cameraman would dolly in for a shot from full-figure to the face of the monster, the uneven floor made it bounce a little and shake a little. He said, ‘I’ve got to do that over,’ and I said, ‘Never. Never! It looks like James Whale shot it!’ Because they had wooden wheels and they were always jumbling and bouncing in those movies, they never had smooth dolly shots. So I said, ‘Let this one dolly shot be a James Whale shot,’ and he finally gave in. I convinced him. I said, ‘They’ll call you a genius for bouncing the camera a little.’”

It’s those little imperfections that sell YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN as a classic of equal standing to the films its riffing on. Although there was a 40-year stretch between the time Brooks’s comedy was produced and the films by Whale, Tod Browning and Val Lewton first captured his heart, those nuances demanded by Mel truly inform the subconscious that you’re watching something on par with those magical early films of the horror genre — even if it’s a loving reproduction.

“I said to Jerry, ‘We have to distress the movie, just like you distress furniture, to give it an ancient and antique appearance,’” says Brooks. “‘We’ve got to distress this movie to make it look like it was 1931.’”

The look of the creature was also a careful consideration. Boris Karloff had made such an impression on the world as Shelley’s frightening-yet-sympathetic abomination of science, with makeup courtesy of the legendary Jack Pierce, that Brooks made an effort to distance himself with his design. With the help of makeup artist William Tuttle, he dropped the signature neck bolts, opting for an amusing zipper instead; relocated the jarring forehead scar to side temple stitches; and opted for a humanizing, bald appearance, rather than a slick-haired, flat head. Brooks elaborates, “One of the reasons I didn’t want it in color was because William Tuttle, another one of the geniuses behind the scenes, said to me, ‘In order to get that look of the monster, he would have to be different shades of green and teal and blue that, in black and white, would all come out to a strange, gray, chalky white, which would be terrifying, which would be the greatest look. But if we did it in color, it would look silly; it would look like a Halloween mask.’”

Of course, you cannot do Frankenstein’s secret laboratory justice without the proper, over-the-top electrical equipment, and Brooks stumbled onto another sprinkle of serendipity to give YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN some serious mad monster credibility. “We got lucky,” he says. “Somebody told me there’s a guy in Santa Monica, he’s still alive, he did the James Whale [FRANKENSTEIN], I think he was 91 or something. … He had a garage, and in the garage were all the special effects, all those machines that they used in the laboratory to create the monster — the electricity, and the wheels with the sparks — the guy’s name was Kenneth Strickfaden. Not only did he have [the equipment], when I came to see him, he plugged it in and it all worked! He said, ‘I kept it up for friends and fans.’ … He rented all his stuff to us, and we gave him a job running it.”

No dummy, Brooks picked Strickfaden’s brain for tips, tricks and anecdotes from the making of the 1931 original that had influenced him so greatly as a kid. “We [watched] the first FRANKENSTEIN together and he said, ‘That slow shot that James Whale used coming around this particular machine using the little lightning gap in the foreground is effective,’ and I said, ‘I’ll steal it. Thank you.’ And I did it. A lot of the James Whale [camera moves and angles], I just took, I shot, you know? Of course I did my own little things…” Showing his appreciation to Strickfaden, he gave the tender Hollywood veteran a special nod in the opening credits.

Lunch breaks during filming also became a special occasion on YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN. “Normally, when I was doing BLAZING SADDLES and I was doing THE PRODUCERS, it was just too exhausting. I’d just have a little cottage cheese and some fruit salad and a coffee and take a nap in my trailer,” shares Brooks. “YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, I was with them every lunch. All of us, Cloris, when Gene Hackman was there, Marty, Gene Wilder and Teri — everybody connected. Everybody in the movie, you know? And I even invited the camera crew, and we all ate together at a big table. It was a family project. Everybody was good.”

Full of rapid-fire jokes and one-liners as well as sight gags, YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN is hugely quotable. The film defies the audience not to laugh, and it turns out the crew had an equally hard time stifling their laughter while capturing certain takes. “There were one or two scenes that we could never get finished,” recalls Brooks with a chuckle. “The one where Marty says, ‘You take the blonde, I’ll take the one in the turban’ — we could never get past that line! The crew would break up. So I finally got a hundred thousand handkerchiefs and said, ‘Stuff this in your mouths!’ Every once in a while I’d turn around and say, ‘I’ve got a hit,’ because there’d be a sea of white handkerchiefs. I knew I had something good. I knew I had something great.”

Summing up the making of YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, Brooks proclaims, “It was one of the best experiences I ever had. I really couldn’t wait to get there in the morning, I loved it so much. … And you know what our biggest problem was? The balance between good story, truth and comedy — never for the comedy to upend it, you know?”

Most filmmakers will tell you that a feature film is never fully done — they just have to walk away at a certain point or they’ll tinker and tweak forever. Asked if he would change anything about the film if he had a chance to go back and rework it, Brooks hesitates. He then responds, “There may have been some Marty Feldman moments in the outtakes; a few little things [I’d put] back in the film.”

A timeless, enduring comedy classic, YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN still lives… Following the smash success of THE PRODUCERS on the Broadway stage in 2001, Brooks was looking to follow it up with another musical adaptation of one of his films. Naturally, he zeroed in on his two most successful products from 1974. But he vacillated between YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN and BLAZING SADDLES, with each film presenting its own unique set of challenges in adapting it to the stage. “It was a tough one,” says Brooks of choosing between his babies, “but I thought YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN would be a more genuinely big Broadway comedy musical. I didn’t know how I would get the [scope of the west] on the stage, you know? Too big. But the laboratory was perfect for the Broadway stage.” The musical production ran from late 2007 to early 2009 on The Great White Way. Now touring, Brooks is planning to open the show in London’s famed West End.

###

MEL’S ‘FRANKENSTEIN’ MEMORIES

Mel Brooks loves to tell stories. One of our all-time favorites is about how, as an impressionable five-year-old, he was terrified of sleeping next to his open window after seeing FRANKENSTEIN — and his mother cleverly calmed his nerves with some practical thoughts. Mel explains:

“It was in July, it’s 1931, and it was hot, and I said to my mother, “Close the window.” And she said, ‘Are you crazy? We’re on the fifth floor right below the roof, it’s 104 degrees in this tenement in Williamsburg in Brooklyn — we don’t close the windows, we’ll die!’ I slept in a little cot right next to the window, which had the fire escape on it, and I said, ‘You’ve got to close the window, Frankenstein’s going to crawl up the fire escape and he’s going to eat me, he’s going to bite me, I know it!’ … My mother was a genius, she was the best — she lost her husband, my father, when I was only two, she raised four boys. She was a heroine. She loved me like crazy, so she sat down on the bed — I’ll never forget (laughs) — and she said, ‘Well, let’s figure this out. If Frankenstein wants to come here, he’s got to get a railroad ticket because he’s in Transylvania, he’s in the middle of Romania or something. I don’t know if they’ll even sell it to him — if they look at him, I don’t think they’ll sell him a ticket. But if they sell him a ticket, he’s got to get all the way on the railroad to a seaport, because there’s no bridge to America. You’ve got to get there by boat. I don’t know if they’d let him on the boat. But let’s say he’s lucky, he sneaks on the boat to America. But he gets to America, he doesn’t even know the subway system. He could never find his way to Brooklyn. He would be completely lost. And let’s say he got here, which is impossible. There are other windows open. He’s not going to wait ’til the fifth floor if he’s hungry to eat somebody. He’s gonna eat somebody on the first floor!’ … I said, “You’re right, open the window.”

###

______________________________________________________________________________

Writing and maintaining IT CAME FROM… is a true labor of love. Please consider showing your appreciation and helping to keep the site ad free and free for all (no paywalls) by donating a couple bucks with BUY ME A COFFEE. It’s quick and easy!